Written by Dumebi Favour Ezekeke

Modern V Traditional Definitions of the African Marke

A market by modern standards, is simply a place where people gather to exchange goods and services. Or, that’s what the textbooks say. But long before economic theories gave it a narrow definition, Africans were already gathering in such places in ways that went far beyond trade.

To many communities across the continent, a marketplace was not just a space, it was a living archive that told stories. A place where storytelling, bargaining and culture balanced on a single rhythm.

The Igbos, in their bonfire stories, captured the essence of the African Market by describing it as a place where the living and the dead crossed paths.

But this spiritual and symbolic idea of the market wasn’t unique to the Igbo. Across indigenous African traditions, markets came with myths, taboos, rituals; stories that often-defied logic and linear time. Some of these markets have not only survived colonization and modern capitalism, they’ve expanded for generations. Like museums without walls.

This article traces the paths of four of Africa’s most symbolic marketplaces and the stories they tell about the people who gather there.

Jemaa el-Fnaa Market of Marrakesh

Loosely translated to mean the ‘assembly of the dead’, the Jemma el-Fnaa market of Marakesh has existed since the 11th Century. Although, it has, over the centuries, taken on many forms. At the time of its establishment, it was regarded as a public execution ground, where rulers made an example of those who defied them. This initial form also gave the market its cryptic name. Over time, however, it shifted roles; from a site of justice to a mosque construction zone (which was never completed) and eventually the bustling marketplace that it is today. Or, as UNESCO describes it, a ‘Masterpiece of Oral Tradition and Intangible Heritage of Humanity’.

As its form has changed over the centuries, so too have the indigenous cultures that trade and gather there. Today, Jemaa el-Fnaa sits at the crossroads of traditional heritage and urban life. During the day, it behaves like any open-air market; a vivid sprawl of food stalls, snake charmers, and vendors showcasing a rather large array of unique goods. You’ll find copperware stacked in shimmering towers, rows of spices arranged in earthen bowls, intricately designed ceramics, and metal plates that catch the sunlight.

But when the night falls, the market changes its rhythm. It becomes a performance ground where storytelling, music, and food take the center stage. There’s also a raw kind of poetry in how the market glows under all the music, lantern lights and chatter of people from different tribes and walks of life.

A large number of the vendors and performers who gather in the square have done so for generations. Chief among them are the Amazigh, or Berber, communities from the High Atlas Mountains and the Sous region. These tribes have a long history of trade in Marrakesh and they bring with them handcrafted rugs, silver jewelry, medicinal herbs, and oral stories passed down through languages like Tamazight and Tashelhit. You would also find the Gnawa people here. Historically regarded as descendants of enslaved West Africans brought into Morocco through the trans-Saharan trade, the Gnawa are known for their hypnotic musical traditions. Their performances, often held in circles, combine elements of Sufi spiritual practice and ancestral memory. They play the guembri; a three-stringed skin-covered lute. Alongside krakebs, which are metal castanets that produce sharp, rhythmic clanging sounds that echo deep into the square. Their ceremonies are less like concerts and more like spiritual awakenings; open, vibrant, and immersive.

The market also hosts traders and craftsmen from rural Saharan communities like the Rahamna, who once served as horsemen and warriors. Today, their descendants continue to contribute to the vibrance of the market with woven goods, regional spices, dyed fabrics, and age-old oral traditions. Though quieter in presence, they remain keepers of cultural memory. Tourists from across Africa and the wider world are drawn to its chaos, colour, and character. But for the locals and indigenous cultures that show up every day, it is simply a regular day at a market square that has been with them for centuries.

Djenné Market of Mali

What we all know today as Mali is an ancient kingdom once known for many things, including its Djenne Market; a trade hub with a long memory. The market is not only recognised for its rich history, but also for the fact that it has opened, and continues to open, only on Mondays since the Middle Ages. The marketplace itself wraps around the city’s mosque and regularly receives traders, buyers and visitors from different indigenous groups including the Fulani herders, Bozo fishermen, Dogon farmers and Bambara herbalists who are known to mix herbs with spiritual elements to create remedies for different ailments.

While the market today might appear like a regular one that simply happens on Mondays, the ground on which it stands carries a deeper history. Oral traditions say the original Djenne settlement, Djenne-Jeno, was abandoned around the year 1000 AD. The site was believed to be cursed — a place of flooding, tse tse flies, and restless spirits. When the new Djenne was founded nearby, it began with an animist ritual. A Bozo virgin was buried alive to appease the spirits and secure peace for the new town. Her tomb, known as Pama Kayamtao, is still believed to carry spiritual significance.

Despite its long history, and the fact that it has been rebuilt, abandoned and rebuilt again, Monday still leads people back to the market. The space is arranged in sections. In one, you might find dried catfish and smoked eels from the Bozo piled high in woven baskets. On another end, Fulani farmers sell livestock and shea butter while Bambara herbalists lay out their roots, powders and leaves said to cure all kinds of ailments. Many believe these herbs are mixed with spiritual properties to make them more effective. If you look closely, you’ll also see shoes, printed fabrics and carved tools that reflect the styles and traditions of the people of Mali.

Today, tourists cross the Bani River by boat or donkey cart to see the mosque at sunset. Those who stay until Monday might find themselves dragged into the chaos that is the Djenne Market. But for the sellers, it is simply a regular Monday where money has to be made.

Kejetia Market of Kumasi

Originally established in the 18th century during the rise of the ancient city of Kumasi, the Kejetia Market has served as a commercial and cultural hub in Ghana for decades. Although it has undergone several phases of expansion; its most notable which occurred in 2015 when efforts were made to modernize its structure without erasing its traditional core. Today, it is regarded as one of the largest open air markets on the continent.

But beyond the rows of beautiful kente stalls and the towers of smoked fish, the Kejetia market system reflects a larger truth about Ghana’s indigenous cultures; particularly the Akan and the Ashanti people. Inside the market, power does not flow from loudspeakers or municipal officials alone. It often begins and ends with the Queen Mothers. These are respected women who preside over trade units, resolve disputes, organize sanitation drives, negotiate with local governments and generally carry out the duties that enable the welfare of the people and the businesses in their trade units.

This tradition within the market mirrors that of the larger Akan worldview; where the queenship exists in tandem with the kingship. According to historical sources, the Queen Mother or Ohema, is regarded as the one who nominates the next chief, advises the stool and guards the moral compass of the community. The fact that these roles have lasted and seeped into the Kumasi’s central market shows just how deeply trade is rooted in the cultural fabric of the people.

While you may not find fire eaters, potions masters or theatrical storytellers here, a walk through the market would expose you to the high-pitched chatter of Twi and Ashanti dialects and as well as pidgin English. Ghanaian fabrics (intricate kente strips and the deep indigo batik known to Ghanaian textile tradition) are often regarded as the soul of the market. But you’d also find shea butter, copper bangles, black soap, jewelry, wooden carved stools and a sea of other goodies. The market is armed with both chaos and order and, if you are not too careful, you could lose your way. And while tourists may visit the market for its scale, most of the traders and locals simply dress up and show up every morning, to a market that has existed with them for so long, it seems impossible to envision the place without it.

Onitsha Main Market

The Igbo often say that the world is a marketplace. While many leave their hometowns to do business in places far from home, many more bring the world to their largest ethnic marketplace: the Onitsha main market. Located on the eastern bank of the Niger River, this market isn’t just the biggest in Nigeria, it is one of the largest open-air markets in West Africa. Its story began long before modern Nigeria was drawn on a map.

The earliest version of the market, known as Otu Nkwor Eze, was founded in the 16th Century during rise of the Onitsha Kingdom. It functioned on a four-day cycle, in accordance with the Igbo calendar. But as Onitsha became a major river port and trade expanded into imported goods, the market evolved into a daily destination. The market has survived colonial interference, war, and fire. It was burnt down and built back after the Nigerian civil war and, in 1916, the British administrators relocated it from the riverbank to its current site inland.

Today, the market stretches across multiple zones in Onitsha, each one with a different tribal name and dedicated to a particular trade. There are sections for electronics, fabrics, jewelry, industrial tools and household goods. The market is loud, vivid and alive. There is the clatter of carts, the thrum of generators, music pouring from phone shops and the buzz of Igbo, Hausa, Yoruba and pidgin English in the air. You may not find ceremonial performances here but, the market itself unfolds like a performance. In many ways, the continued growth and expansion of the Onitsha Main Market and its ability to rebuild itself time and time again is a reflection of the Igbo character. It mirrors their capacity to rise from hardship and create enterprise from scratch. It also reflects the commercial spirit of the Igbos which is not limited to Onitsha but travels with the Igbos who are scattered across Nigeria and beyond.

Tourists may come to observe the chaos and size of the market. But for the thousands who show up each morning, it is simply a regular day in a market that has grown with them for generations.

The real transaction lies in the stories.

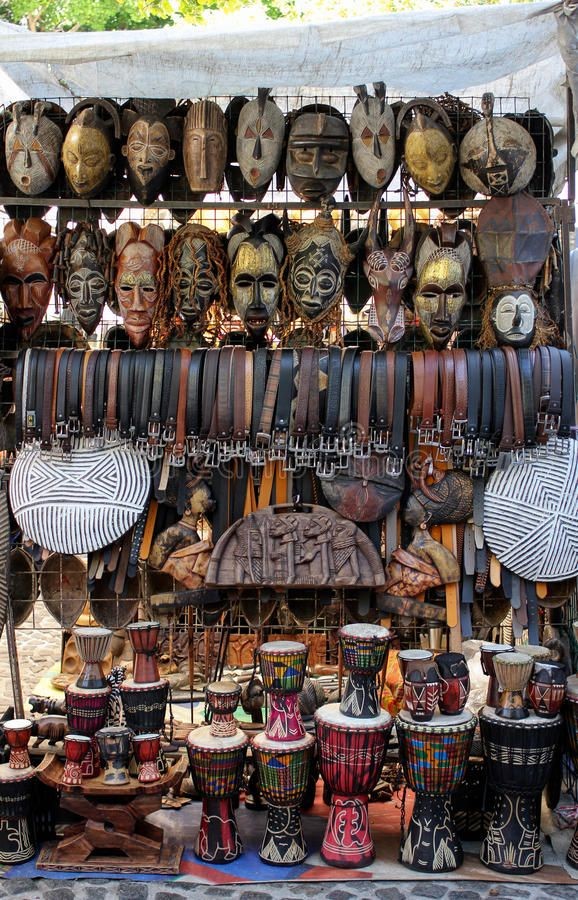

Beyond the markets mentioned, there are countless others scattered across Africa that hold memory beyond the daily exchange of currency for goods. From the stone wall markets in Zanzibar to the craft markets in The Gambia. From Kariakoo in Tanzania to Makola in Accra, and the centuries-old Soumbédioune in Senegal; these places remain rooted in tradition.

Next time you dress up to buy things from an African market, don’t just rush in and rush out. Observe the buzz. Listen to the chatter. Look around for the people who have been there forever. And if you look deep enough, you may see the museum that it is. One that you can enter for free, to learn something about the indigenous cultures that came before the market itself.

SOURCES

Bonnier, E. (n.d.). Morocco – Marrakech souk. Erick Bonnier Pictures. Retrieved June 24, 2025, from

https://www.erickbonnier-pictures.com/reports-travels/morocco-marrakech-souk/

Kanaga Tours. (n.d.). The mosque and the Monday market in Djenne. Kanaga Africa Tours. Retrieved June 24, 2025, from

https://www.kanaga-at.com/en/trip-info/mali-en/the-mosque-and-the-monday-market-in-djenne/

Schmitt, T. (2005). Jemaa el‑Fna Square in Marrakech – Changes to a Social Space and to a UNESCO Masterpiece of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity [PDF]. Arab World Geographer, 8(4), 173–195. Retrieved from

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/274256696_Jemaa_el_Fna_Square_in_Marrakech

Oma. (n.d.). Some superstitions & traditions that exist in Igbo communities. Oma’s Garden Blog. Retrieved June 24, 2025, from

https://sloaneangelou.blog/journal/some-superstitions-amp-traditions-that-exist-in-igbo-communities

UNESCO. (2001, November 29; 2008). Cultural space of Jemaa el‑Fna Square. UNESCO Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity. Retrieved from

https://ich.unesco.org/en/RL/cultural-space-of-jemaa-el-fna-square-00014

UNESCO. (2019). Gnawa music of Morocco [Intangible Cultural Heritage nomination]. UNESCO Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity. Retrieved June 24, 2025, from

https://ich.unesco.org/en/RL/gnawa-01170

UNESCO World Heritage Centre. (n.d.). Old Towns of Djenné. UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Retrieved June 24, 2025, from

https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/116