Written by: Dumebi Favour Ezekeke

Are dolls mere toys?

African girls of the 21st century, like me, still vividly remember our Barbie years. Yes. That period when a doll and a string of cartoons sparked an entire era of pop culture, music, beauty, and fashion standards. At the time, our interactions with these dolls seemed harmless. Barbie dolls came across as a beautiful and incredibly cool representation of a female lead character we saw on our screens.

But I remember wishing my Afro hair could grow long and silky like Barbie’s. I wished my waist could shrink into the kind of figure that let you wear Barbie’s outfits. I wanted the songs, the sparkle, the fantasy. And I know I wasn’t the only one.

In fact, the Barbie culture ran so deep that it seeped into celebrity culture and mainstream music. Nicki Minaj, for instance, continues to embody what a “real-life” Barbie should look like. And at the time she took on the name, girls like me; watching from the other side of the screen, saw her as proof that Barbie could be real. But the sad part was, she still didn’t look like the average Black girl. These dolls carried quiet messages about what beauty should be. And somehow, we were made to feel wrong for not being a part of it.

This reflects the deeper truth about dolls and their significance; they are not just toys.

They are symbols. And Barbie is not the only one that has carried this kind of weight. Long before her, African doll-making was a practice deeply tied to womanhood, fertility, ancestry, and identity. But the message of “civilization” that colonialism brought along branded these traditions as primitive. It called the craft “witchcraft” and erased it from cultural memory.

But what did we lose when we stopped making our dolls?

What stories did traditional African dolls tell?

Unlike the average Barbie or commercialized dolls found in markets today, African traditional dolls rarely aimed to replicate the female body or push any standards of what physical beauty should look like. Even though the process itself was often an art passed down from mother to child. In many parts of Southern Africa, for instance, girls were taught by older women (usually their mothers) in their families, to sew, crochet and design clothing for their dolls. According to the Australian Institute of Arts, this early engagement of doll making for young girls helped in shaping their abilities to imagine, create or express themselves.

In other words, under such circumstances, the doll itself (or what it should look like) was never the issue. It was the act of creating that mattered. Doll making wasn’t just about shaping creative processes. It was also about giving young African girls a sense of belonging. Like; ‘I am allowed to create what I play with and not just buy it off the market’. Read that again.

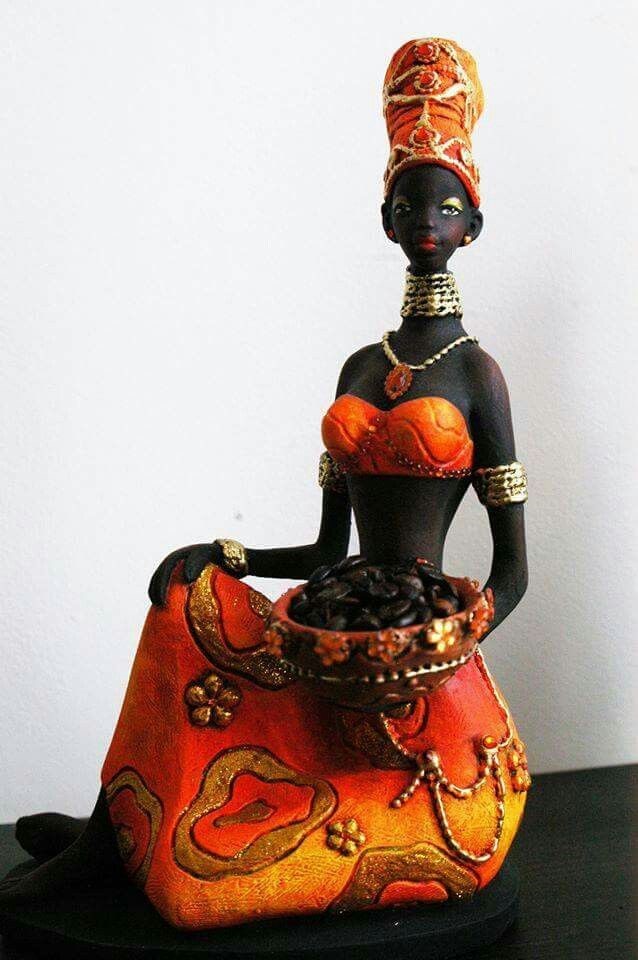

This freedom meant that no two dolls had to look alike. Some had elongated necks stacked with beads. Others had exaggerated heads or no facial features at all. Some were wrapped in fabric with intricate patterns, while others were carved from wood and adorned with cowrie shells. They didn’t come out of factories, they came out of the mind. This may be one of the reasons why it was easy (especially under colonial and missionary eyes), to look at these dolls as figures of witchcraft and not as symbols of cultural and creative exploration.

The creative exploration of female identity through traditional doll-making was only one version of its significance. Dolls were also often deemed as gifts, goodluck charms and symbols of deep cultural and spiritual meanings. Some notable examples of such dolls includes:

- Ndebele Dolls:

Deeply rooted in the Ndebele culture of Southern Africa, Ndebele dolls were not just symbols of tradition, but of femininity itself. They were often gifted to young girls by their mothers or grandmothers at different stages of life. And because of this, the dolls came in different variations. There were dolls for fertility, for coming of age, for ancestral lineage, and for spiritual connection to the community. Each one marked a moment. Each one carried a message. They were the clearest depiction of what Ndebele femininity looked like, or what a woman was expected to grow into as she got older.

- Ere Ibeji Dolls

Alternatively known as ‘twin memorial dolls’, the Ere Ibeji are deeply rooted in the Yoruba tradition of Southern Nigeria. They were often sculpted after the death of one twin, not as toys, but as spiritual placeholders. These dolls were never played with. Instead, they were cared for by the mothers as if they were the living child. Many times, the mothers bathed the carved figures in special oils, dressed them, fed them, and even danced with them during festivals. The making of these dolls was rooted in the belief that twins share one soul. So, when one passes, it becomes necessary to create another figure to maintain spiritual balance between the twins, regardless of the distance or realm one of them may have crossed into.

- Namji dolls

Namji dolls of Cameroon also held deep cultural and spiritual significance, much like the Ndebele dolls. These dolls were often given to brides on their wedding day as symbols of good fortune during childbirth. They were carved from wood and adorned with beads, cowrie shells, and sometimes coins. Each item is believed to carry spiritual or fertility power. Some were also given to young girls, who cared for them like real children, learning early how to nurture and take responsibility. More than just symbols of motherhood, Namji dolls carried the spiritual weight of femininity in the Namji culture.

How African Traditional Dolls became witchcraft

The answer to this question can be summed up in one word; colonialism.

Sure, in our history and government classes back in secondary school, most of us were told that colonialism was justified because it came to ‘civilize’ the so-called primitive cultures and practices across Africa. But the other side of that story (the one we were rarely told) is how many traditions that once held deep cultural significance were erased almost completely. Doll making was not left out of this.

In this context, the earliest wave of colonial influence actually came through missionary activity. With the spread of Christianity, rituals and cultural festivals that involved doll making or doll gifting, especially those tied to fertility, womanhood, or spirituality, were suddenly branded as forms of sorcery. In Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe), the 1899 Witchcraft Suppression Act for instance, didn’t just target ritual practices; it criminalized objects, tools, and processes that were tightly bound to African identity. This included the art of doll making and the dolls themselves. Similarly, in places like Kenya and parts of Nigeria, laws were enacted that criminalized spiritual and cultural artifacts once held sacred by communities.

Over time, the term ‘witchcraft’ became a blanket label for anything unfamiliar to colonial missionaries or anything that couldn’t be neatly explained through Christian doctrine.

But this shift didn’t just rename the dolls; it erased their context entirely.

All of their spiritual and symbolic value was grouped under terms like idolatry or sorcery. Some traditional groups that actively practiced doll making were also cast out and demonized. For example, the Nyongo society in Cameroon was accused of ‘using dolls and charms to traffic souls’, and the entire system was eventually dismantled.

What makes this even more ironic is how, decades later, after African countries were deemed ‘modernized’ enough, commercial dolls from the West (like Barbie, Russian nesting dolls, and others) were reintroduced and sold across African countries. These dolls, though foreign and mass-produced, were marketed to girls as stylish, desirable, and aspirational. And somehow, they were no longer seen as occultic but as trendy. Even people who had long been taught to fear idols now gifted these toys to their daughters and loved ones, never once questioning what messages they carried or what they could quietly plant in a girl’s mind.

Where is African Doll Making Today?

In the words of Thomas Sankara, “We must unlearn the shame we were taught to feel about ourselves and relearn how to accept, honour, and take pride in who we are.” That shame didn’t come from nowhere. It was handed down, systemically, by those who told us our own traditions were something to run from. And that is exactly what happened to African doll making.

This article is not just about the dangers of erasing African symbolism through objects like its dolls. It is about the quiet shame we were taught to carry. The way we were told to turn away from the things that belonged to us and to reach for things that were never made with us in mind. We were told to stop making, stop playing, stop believing in what was ours. And instead, we were handed half-made ideas of beauty, identity, and womanhood, then left wondering why we were never considered in the creation process.

The truth is, not everything created or celebrated in traditional African cultures was demonic, satanic, or primitive, as we were told. Just like the procedures in South African doll making, many of these practices were not just tools for home training, but tools for building identity, confidence, and care. They were deeply tied to the development of girls, to the strength of community, and to the sacred work of remembering where you come from.

So where is African doll making today?

It still exists; in corners, in memory, in fragments held by those who never forgot. But maybe it’s time we looked behind the curtain and saw it again for what it truly was. Something to be found and celebrated, not feared.

REFERENCES

Ardener, E. (1956). Images of Nyongo amongst Bamenda Grassfielders in Whiteman Kontri. Citizenship Studies, 9(3), 241–269.Retrieved from: https://doi.org/10.1080/13621020500147319 https://www.researchgate.net/publication/229014783_Images_of_Nyongo_amongst_Bamenda_Grassfielders_in_Whiteman_Kontri

Chronicle. (2014, March 3). Witchcraft Suppression Act undermines culture, tradition. The Chronicle.

Retrieved from: https://www.chronicle.co.zw/witchcraft-suppression-act-undermines-culture-tradition

Girl Museum Inc. (2017, November 28). Girl of Beads: Ndebele Doll. Girl Museum.

Retrieved from: https://www.girlmuseum.org/ndebele-doll

Hadithi Africa. (2020, May 23). African Fertility Dolls. Hadithi Africa.

Retrieved from: https://hadithi.africa/african-fertility-dolls

Human Rights House Foundation. (n.d.). Spectre of witch hunts in Zimbabwe. Retrieved from: https://humanrightshouse.org/articles/spectre-of-witch-hunts-in-zimbabwe

Smithsonian Institution. (n.d.). Beaded Ndebele doll [Object record, NMAfA 2000-27-5]. National Museum of African Art. Retrieved from: https://www.si.edu/object/doll:nmafa_2000-27-5

Smithsonian Institution. (n.d.). Beaded Ndebele doll [Object record, NMAfA 83-12-26]. National Museum of African Art. Retrieved from: https://www.si.edu/object/doll:nmafa_83-12-26

The Met Museum. (n.d.). Twin Figure (Ere Ibeji), Yoruba people. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved from: https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/318573

Veritas Zimbabwe. (n.d.). Witchcraft Suppression Act [Chapter 9‑19]. Retrived from: https://www.veritaszim.net/sites/veritas_d/files/Witchcraft%20Suppression%20Act%20%5BChapter%209-19%5D.doc

Wikipedia contributors. (2024, May 15). Nyongo society. Wikipedia.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nyongo_society

Wikipedia contributors. (2025, July 1). Witchcraft Suppression Act, 1957. Wikipedia.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Witchcraft_Suppression_Act%2C_1957

World’s Window KC. (n.d.). What’s the story? Namji dolls. World’s Window Kansas City.

Retrieved from: https://worldswindowkc.store/pages/whats-the-story-namji-dolls