Written By: Dumebi Favour Ezekeke

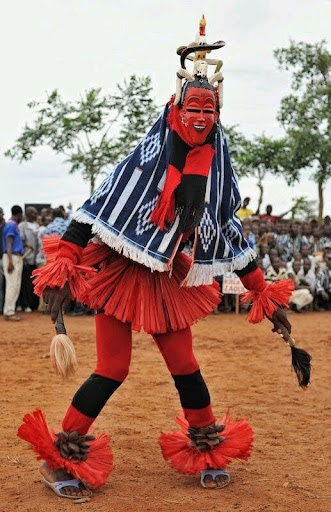

If you were an avid follower of the iShowSpeed Africa tour, like me, you probably noticed that when he got to Cote d’Ivoire, he danced alongside a towering figure dressed in a striped bodysuit, crowned with a brightly colored mask. The figure’s ankles were heavy with strung bells or seed pods, and layers of raffia skirts shook with every movement. Together, both bodies launched into a dance that puts the popular Nigerian “legwork” to shame. Rightly so.

The dance is called Zaouli, and it is regarded as one of the hardest dances in the world, even though it might not seem that way at first glance. While the dancer’s legs moves in rhythms so tight they appear almost repetitive, no two steps are ever repeated at the same time. The feet blur, dart, stamp, and slide with mechanical precision, demanding breath control, balance, and endurance all at once. An average dancer in training takes up to seven years to fully master the form and perform it seamlessly.

But before jumping the gun on the dance itself and its significance, we have to take a few steps backwards, to the beginning.

Where did Zaouli come from? Why are different Ivorian masks used for different dancers? What kind of dance is it, really? Is it passed down from family to family, or can any Ivorian who feels called to it take the training and begin to dance? And finally, why is Zaouli so revered in Ivory Coast?

Pronounced “Zawli,” Zaouli is a masked dance created in the 1950s by the Guro people of central Cote d’Ivoire. The Guro, part of the larger Mande ethnic group in West Africa, were traditionally known as Kweni; entertainers whose performances blended spectacle, storytelling and social commentary. Unlike older ritual dances tied strictly to spiritual rites, Zaouli was created as a unifying performance. It was inspired by the beauty and grace of a young girl named Djela Lou Zaouli, after whom the dance was named. Its other name, Djela Lou Zaouli, literally means Zaouli, the daughter of Djela. Although the dance celebrates feminine beauty, it is majorly danced by men. Zaouli is most popular among the Guro communities of the Bouaflé and Zuénoula departments. In a single performance, it brings together sculpture, weaving, music, and dance. The key element which sets the dance apart, however, are its masks.

Zaouli Masks

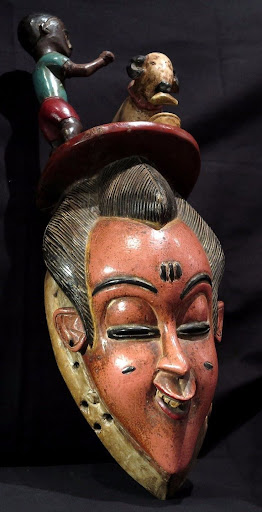

In the Guro world, masks carry deeper meaning than mere objects. They represent history, identity and decades of shared memory. This means that, whenever a dancer wears a Zaouli mask, he is not just performing. He is reliving and retelling the stories that built his community. The shape of the mask, its color and superstructures carry tales or idea which are brought to life through the dance.

According to Zaouli tradition, there are seven types of masks used for the dance. However, its most prominent are three namely; Zohoulin, Gan and Sortavani.

Zohoulin is often one of the first masks people see. Its color and iconography can vary, but one story describes its imagery as a grey mask with a scene of a chicken eating a lizard. In that version, the chicken represents the Guro people and the lizard represents their rivals. The image is a symbolic reminder of past conflicts and victories, a way of honoring cultural strength and resilience.

Gan, on the other hand, brings a different kind of energy. Its bold red face and set of horns symbolize strategy, agility, and survival. One interpretation suggests that the horns represent the tactics of antelope escaping hunters, a metaphor for cleverness and adaptability in life. This mask carries a sense of strategy and movement that matches the dancer’s own shifting, lightning-quick rhythm.

Lastly, Sortavani is vivid in orange and calls attention to the artistry and labour of the weavers in Guro society. Textiles and weaving are essential parts of community life and identity, and this mask honors that craft. Wearing Sortavani in performance is like giving voice to the quiet, skilled hands that shape the everyday cultural fabric of the people.

Little information has been provided about the other masks, beyond these three. However, it is indisputable that these masks go beyond idealized beauty. They are composite beings. Many carry birds, snakes, or other figures on top of the face, and each of these symbols adds another layer of meaning. For instance, birds might signal freedom or spiritual connection. Snakes can be signs of knowledge or transformation. All of these elements come together when the mask is worn and the dance begins.

Zaouli Dancers in Training

The Zaouli dance is regarded as one of the hardest dances in the world for a reason. Learning it is not just about memorizing steps; it is about transforming your body into rhythm itself. Apprentices spend years under the watchful eye of a master, watching, mimicking, and slowly building the stamina, balance, and precision required. Every leap, pivot, and stamp of the feet must sync perfectly with the bells on the ankles and the rhythm of the music. What looks effortless on stage is the result of countless hours of repetition and discipline. Even after years of training, mastery is never complete. The mask changes everything. Once a dancer dons it, he becomes more than a body in motion; he becomes a vessel carrying the history, stories, and pride of his community. Zaouli is not just hard physically; it is a lived transformation, demanding focus, patience, and respect for a tradition that stretches back generations.

Don’t miss a thing! Sign up to get new content sent directly to your inbox.