Sophia El Bahja: Through the Lens of Heritage and Modernity

Some photographers capture beauty. Others, like Sophia El Bahja, capture meaning Her images are not just visuals.

Some photographers capture beauty. Others, like Sophia El Bahja, capture meaning Her images are not just visuals.

If you ask ten different Africans what waist beads mean, you’ll likely hear ten different answers. But some common replies are:

In Ethiopia, a wedding is never just a ceremony; it is a grand symphony of tradition, faith, family, and festivity.

When people think about skincare these days, the first thing that comes to mind is usually high-end luxury brands like La Mer.

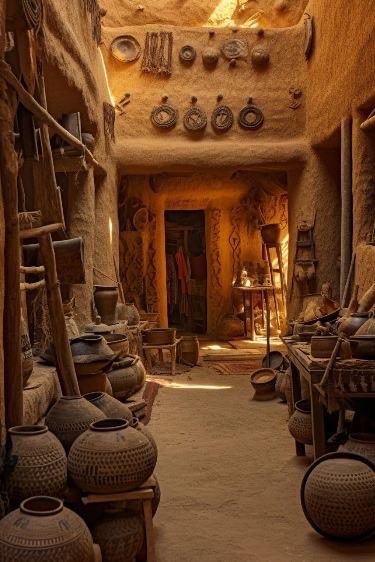

A market by modern standards, is simply a place where people gather to exchange goods and services. Or, that’s what the textbooks say.

In Africa, the calendar is not just measured in months or seasons but also in gatherings. A year feels unfinished if you haven’t stood in a crowded.

What if the best way to understand Africa was through movies? African cinema tells stories of struggle, survival, love, politics, and dreams.

On the 26th of July, 2025, Grammy-winning singer Ciara shocked the world again. Not with a new single or a popular dance trend, but by becoming.

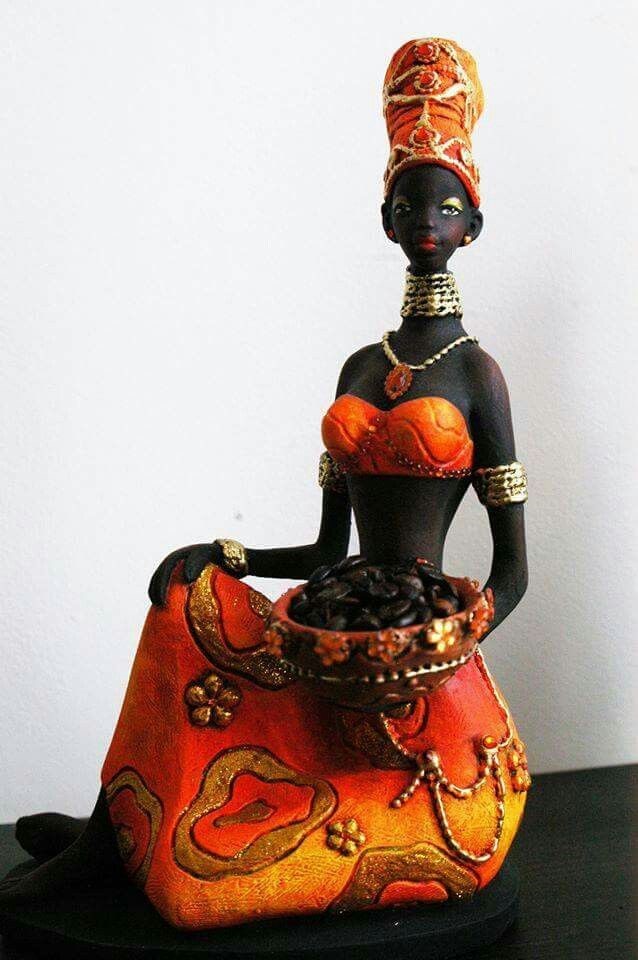

African girls of the 21st century, like me, still vividly remember our Barbie years. Yes. That period when a doll and a string of cartoons sparked.

There’s a kind of African who will argue with a market woman or their Uber driver over 50 rand, 2,000 francs, or 1,500 naira then walk into a restaurant.