Ouma Katrina Esau and the Fight to Keep N|uu Alive

Once spoken freely across the arid plains of the Northern Cape, N|uu predates all languages by thousands of years.

Once spoken freely across the arid plains of the Northern Cape, N|uu predates all languages by thousands of years.

Kalu David, the creative force behind DavidBlack, a Lagos-based fashion brand, insists that every piece deserves intention, artistry, and meaning.

Adire (ah-DEE-reh) – A Yoruba word, “adi” (to tie) and “re” (to dye) translates to tie and dye. The weight of what Adire truly gives is an art form, a language.

There’s a particular quality to the air when summer settles in. It’s like a promise. The cities feel looser, the music a little louder, the skin more confident.

In Somalia, poetry was more than art. And at its heart stood the Gabay, a grand, rhythmic battle of wits, pride, and power.

“I knew I wanted to be an architect since I was 8 years old,” she once said, recalling a childhood filled with sketching, tinkering, and curiosity.

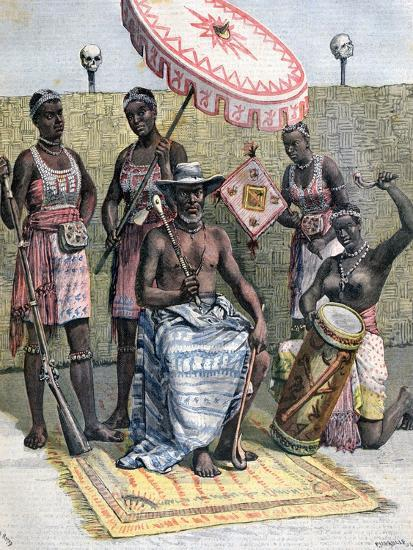

Before European empires divided Africa with pencils and treaties, the continent was a constellation of kingdoms. Some born in the shadows.

Ouidah, Benin. The kind of place that breathes history. That’s where she was born in 1960, in a home full of sound. Her mother ran a theatre troupe.

In Eastern Nigeria, a grandmother leans over a pot of simmering egusi soup, instructing her granddaughter in measured, melodic Igbo:

Every African man remembers a game. Not just one they played, but one that shaped them. In a dusty compound in Kano, boys chase each other through.