Written by: Kemi Adedoyin

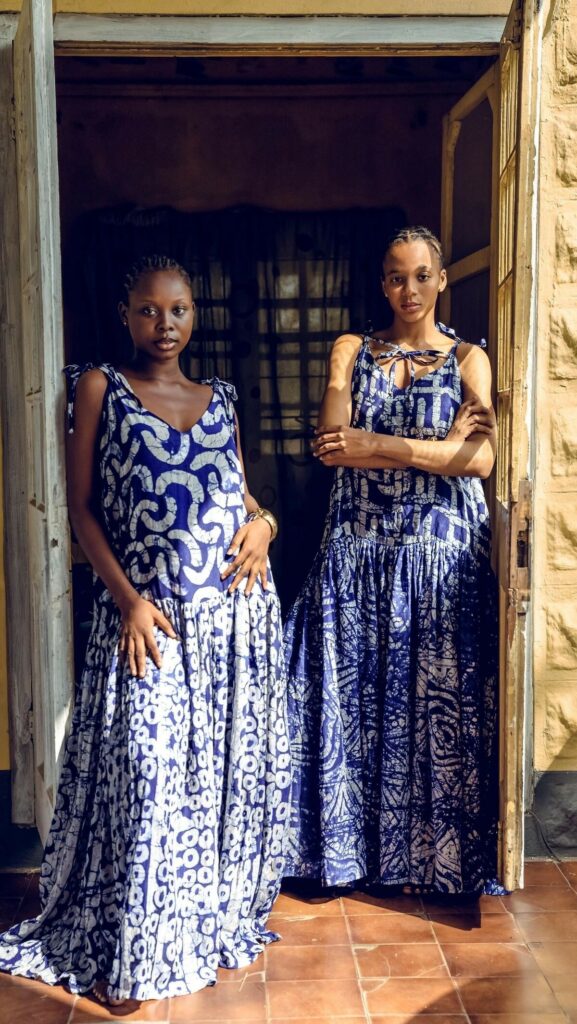

Adire (ah-DEE-reh) – A Yoruba word, “adi” (to tie) and “re” (to dye) translates to tie and dye. The weight of what Adire truly gives is an art form, a language without alphabets. It is history, crafted by women.

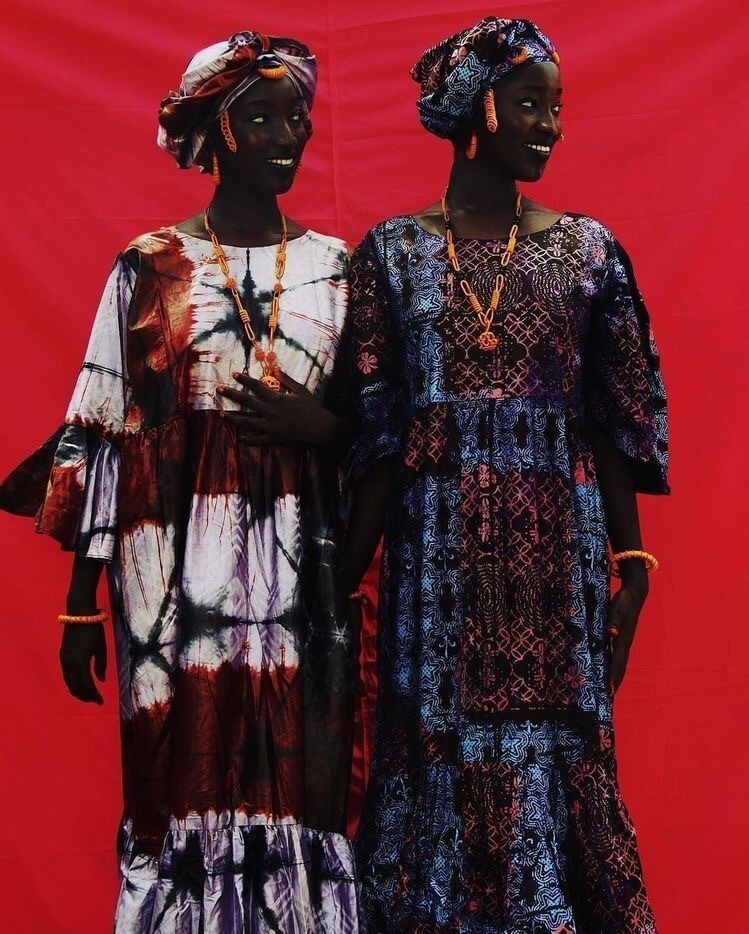

Today, Adire hangs in global fashion showrooms, parades through Instagram feeds, and sells in open markets across West Africa. But something feels off. A closer look at these prints, the slick polyester feel, and then the label: Made in….

We are now importing the very thing we invented.

Before Adire came into the cultural wardrobe of the Yoruba people, indigenous clothing leaned heavily on Aso-Oke, Etu, and Sanyan, rich handwoven fabrics that signified social status and occasion. These were often worn during ceremonies and rites of passage, carrying as much spiritual significance as aesthetic.

Clothing for Africans wasn’t just about covering the body, it was storytelling, identity, and pride. So when Adire was born, it didn’t replace the old ways. It extended them.

Adire began in Abeokuta, Nigeria, in the early 20th century, pioneered by Yoruba women, especially members of the Egba tribe. These women were textile traders and artists, especially the Aladire (a professional decorator for adire), who combined local innovation with foreign influence.

How? When Europeans introduced imported cotton into West Africa, Egba women saw potential. Instead of wearing it plain, they dyed and decorated it using onko (local indigo), raffia ties, cassava paste, and feathers to create patterns.

While Abeokuta in Ogun State is widely credited with pioneering its popularization, especially through Egba women, many in Osun State also claim origin. Cultural figures from Osogbo argue that Adire existed in various forms long before colonial trade routes, pointing to Osun’s spiritual depth and longstanding dyeing traditions.

Adire was born out of creativity, trade, and cultural evolution. It was women-led. Women-owned. Women-powered.

The Process

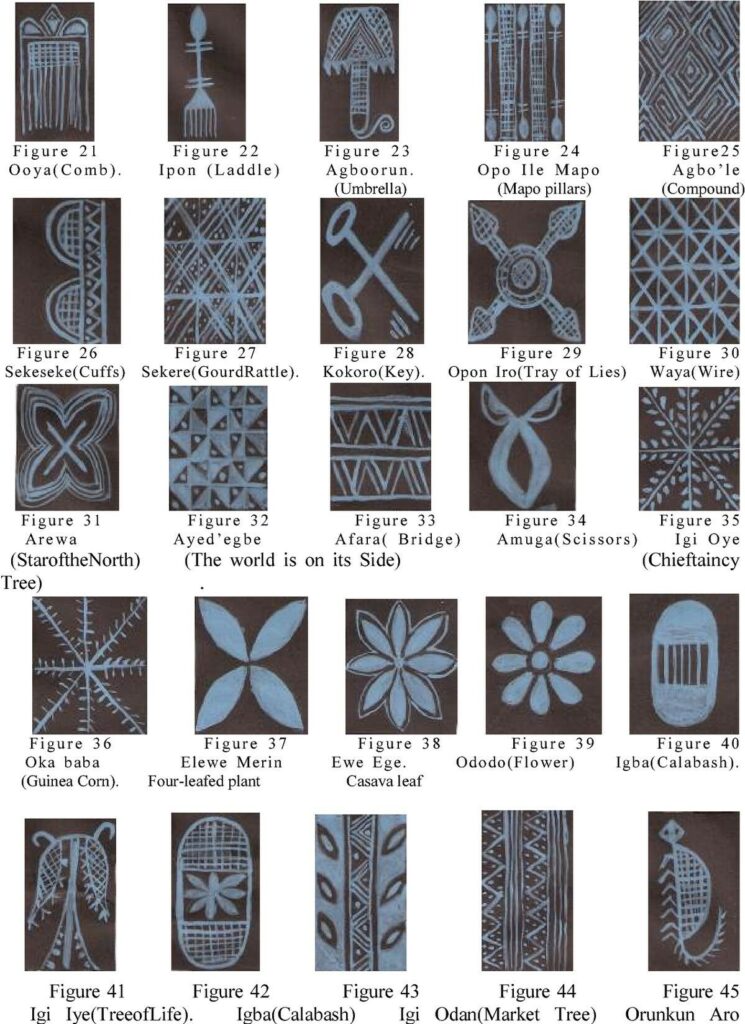

True Adire is hand-dyed using natural indigo dye extracted from plants like Elu (Indigofera). There are three main techniques:

● Adire Oniko: tying parts of the fabric with raffia or thread before dyeing.

● Adire Eleko: applying cassava paste to draw motifs that resist the dye.

● Adire Alabere: stitching patterns with thread that are removed after dyeing.

Each design holds meaning. For example, Ibadán dun (“Ibadan is sweet”) means a celebration of pride and city identity.

A System Built Around Women

At its peak, Adire was a thriving industry driven by female collectives. In Abeokuta, Ibadan, Osogbo, and beyond, entire families were sustained through Adire production. Young girls apprenticed with their mothers. Markets buzzed with women selling freshly dyed cloth. It wasn’t only culture, it was commerce as well.

Fast forward to today, and the story is far more brittle.

Imported Adire knockoffs that are synthetic and mass-printed are now flooding African markets. These fakes are falsely branded as “African prints.” And these results to

● Local dyers losing customers.

● Mothers no longer teaching the trade as it’s no longer profitable.

● Whole families who once relied on Adire are turning to other forms of crafts

The very communities that built this heritage are now priced out of it.

Imitation Crisis Might Continue

It’s easy to talk about globalization and access, but what we’re witnessing isn’t only expansion, it’s cultural theft under economic pressure. Originality is replaced by replication, and even worse, many buyers, especially in diaspora communities, can no longer tell the difference. Imagine a child wearing Adire to an Independence Day parade, not knowing the cloth was printed in a factory, not in the same country whose independence they are celebrating.

What We Lose as Africans

● Craftsmanship: The years of apprenticeship it takes to master resist dyeing can’t be replicated.

● Local enterprise: Women-owned Adire businesses once sent children to school, built homes, and supported extended families.

● Intergenerational knowledge: Without demand, no one learns. The skills vanish.

● Cultural authority: We lose control over how our identity is represented and reproduced.

Preserving Adire Is Preserving People

Preserving Adire is to protect the ancestral knowledge stitched into every design. Here’s what it takes:

1. Invest in Local Artisans: Government and private initiatives must go beyond festivals and fashion shows. Invest in Adire cooperatives, provide access to raw materials, and offer export support for authentic African products.

2. Cultural Education: Teach young Africans not just how to wear Adire, but how to recognize real from fake.

3. Creative Collaboration with Boundaries: We welcome innovation. But collaborations must center and credit local artisans. Global designers can work with African dyers without erasing them.

4. Shift Our Mindset: We must stop viewing African products as inferior unless validated abroad. If our people produce it, it matters. It’s premium. It’s powerful.

What We Keep, Keeps Us

Culture and Heritage don’t vanish all at once. It fades when the small things stop mattering, when we stop asking where our fabrics come from, who made them, and what they were meant to say.

Adire is still here. Not as a trend, but as a thread, that is, one that connects us to meaning, to one another.

So we don’t need to shout to preserve it. We just need to choose it. To keep buying what’s made with care. To honour the hands behind the work. To teach the stories behind the cloth.

Because when we protect what’s ours, we don’t just preserve heritage, we pass on something worth inheriting.

And that, too, is legacy.

Don’t miss a thing! Sign up to get new content sent directly to your inbox.