Before European empires divided Africa with pencils and treaties, the continent was a constellation of kingdoms. Some born in the shadows of volcanoes, others carved into the savannahs by sword and spirit. One of the fiercest was Dahomey, a kingdom that stood where present-day Benin now lies. Its walls were high, its rituals sacred, its women warriors feared. And at the center of its final roar stood a king, Béhanzin, who would go down in history not just as Dahomey’s last ruler, but as its last independent one.

Before the Kingdom: A Land of Lineage and Fire

Long before Dahomey rose, southern Benin was home to the ancient Yoruba-speaking kingdoms of Allada, Porto-Novo, and Whydah, states that traded, worshipped, and warred along the West African coast. These weren’t kingdoms in name only. They had structured governance, complex belief systems rooted in Vodun, and thriving commerce with Europeans as early as the 15th century.

When the royal prince Do-Aklin fled Allada in the early 1600s, he sought sanctuary in the inland plateau. What began as refuge became revolution. His descendants founded the royal city of Abomey, and with time, a kingdom unlike any other began to emerge. Its name? Dahomey. Born, as legend has it, after the king built his palace atop the grave of a rival chief and named the land “Danxomé” or “in the belly of Dan.”

The Making of an Empire

Founded in the early 1600s by displaced royalty from Allada, the Kingdom of Dahomey was born of exile and ambition. Its capital, Abomey, soon became the spiritual and political heart of the kingdom, fortified by red clay walls and lined with palaces carved with royal symbols: sharks, lions, swords, drums.

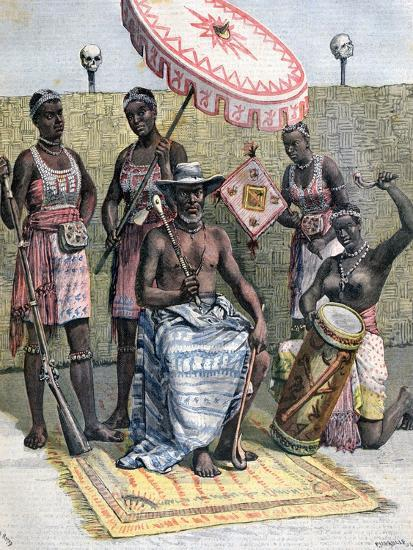

By the 18th century, Dahomey had risen to regional dominance, capturing coastal kingdoms like Whydah and inserting itself into the transatlantic slave trade. Its leaders were feared for their military innovation, their calculated diplomacy with European traders, and their commitment to tradition. At the height of its power, Dahomey had one of the most unique features in world history- an all-female military regiment, known in Fon as the Agojie, or as the West came to call them, the Dahomey Amazons.

The Amazons of Dahomey: A Nation’s Blade

The Agojie, often called the Dahomey Amazons, were an elite corps of female warriors. Disciplined, brutal, and unwaveringly loyal to the throne. They fought with rifles, machetes, and courage that rivalled any man. Recruited in childhood, forbidden from marriage, these women lived only for the kingdom.

Foreigners could hardly believe what they saw. To the French, they were “terrifying.” To the kingdom, they were protectors, priestesses, and legends. When battle drums beat through Abomey, the Agojie were the first to march. And when the enemy approached, they didn’t blink.

In 2022, the story of the Agojie burst into global consciousness with the release of The Woman King, a historical drama directed by Gina Prince-Bythewood and starring Viola Davis as General Nanisca. While fictionalized in parts, the film draws directly from the traditions and legends of the Agojie and the real-life reign of King Ghezo, Béhanzin’s father.

How Kings Were Crowned in Dahomey

Royal succession in Dahomey wasn’t simple. Blood alone wasn’t enough. When a king died, candidates, often sons or brothers, were vetted by royal ministers and spiritual leaders. The Migan (head minister) and the Queen Mother played crucial roles, balancing political strategy with ancestral will. The new king would undergo sacred rituals and receive a royal emblem, often an animal, that symbolized his essence.

This was not just politics. It was prophecy.

King Béhanzin: The Last Flame of Sovereignty

Béhanzin was born in 1844, the eleventh son of King Ghezo, a ruler remembered for expanding Dahomey’s power and modernizing its army. Groomed from an early age for leadership, Béhanzin was said to be fiercely intelligent, strategic, and unwavering in his convictions. His royal symbol was the shark, a creature that never stops moving forward-an omen, perhaps, for a king who would never yield.

When he ascended to the throne in 1889, colonial pressures were tightening like a noose. The French, under the guise of treaties and trade deals, were already staking claims to West African territories. Béhanzin saw clearly what others tried to ignore: the Europeans didn’t want partnership, they wanted possession.

Béhanzin’s reign would last only five years, but every moment of it was on fire.

He immediately rejected France’s claims over Cotonou, an important port they said he had ceded under his father. Béhanzin saw it as theft, and he prepared for war.

Thus began the Second Franco-Dahomean War (1892–1894), one of the most fiercely fought anti-colonial wars of the 19th century. Unlike many African leaders who tried to compromise or delay confrontation, Béhanzin met France head-on. His army, though less technologically advanced, fought ferociously. The Agojie, still the kingdom’s frontline soldiers, attacked French columns in coordinated raids, shocking European commanders with their discipline and valor.

But the French had one thing Dahomey didn’t: machine guns. Béhanzin’s warriors, brave as they were, faced repeating rifles and Maxim guns that tore through regiments. Even so, Béhanzin refused to surrender.

And even as Abomey was eventually captured, Béhanzin refused to sign any treaty that legitimized French authority. Instead, he set fire to his royal palaces, retreating with his remaining soldiers to the north, keeping resistance alive.

After the Kingdom

Following Béhanzin’s exile, the French installed a puppet ruler, Agoli-Agbo, Béhanzin’s relative. But he was king in name only. Dahomey was formally annexed into French West Africa in 1904, becoming just another colony on a European map.

When independence finally came in 1960, the new republic called itself Dahomey, in honor of the fallen kingdom. But in 1975, the name was changed to Benin, a nod to the broader cultural groups in the region and a desire for national unity.

Still, Dahomey is not forgotten. The royal palaces of Abomey remain sacred ground. The memory of the Agojie lives on. And Béhanzin? His name is whispered with reverence.

Béhanzin’s resistance was not in vain. It was a spark that would light future fires of nationalism, decolonization, and cultural pride. His decision to burn his own palace rather than let it fall into enemy hands speaks volumes: some things are too sacred to be conquered.

Today, he stands among Africa’s great anti-colonial leaders not just as a footnote in French conquest, but as a symbol of dignity, resistance, and unyielding identity.

Written by Kemi Adedoyin

Don’t miss a thing! Sign up to get new content sent directly to your inbox.